Gesture as a Hinge. From East Berlin, 1989, to Gezi Park, 2013, to Tehran, 2022

A conversation between Elske Rosenfeld and Burak Üzümkesici

This text was first published in Turkish on the feminist website https://www.5harfliler.com/dogu-almanyadan-geziye-jestler-ve-toplumsal-mucadelelerin-dili-elske-rosenfeld-ile-soylesi/ in April 2023

Read MoreBurak Üzümkesici – Your work “A Vocabulary of Revolutionary Gestures” is an exploration of the ways by which we remember and make sense of social movements or historical turning points. It takes its materials from quite different historical moments, ranging from the last days of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1989/90, to the Gezi Park protests of 2013, or the so-called Arab Spring from 2011 onwards. The primary concern of your work is the “embodiment of revolt and revolution” and you seek this embodiment in what you call “revolutionary gestures”. You seem to be suggesting that there is a distinct grammar offered to us by these events, and that we don’t yet have the means to speak this particular language, or that we don’t yet know what to do with the elements of this language. If I am not mistaken, you have been working on this project on a regular basis since 2013 – and you showed a selection of four works as part of the multi-part, site-specific installation “Archive of Gestures” at last year’s Berlin Biennial. What was your initial point of departure, and how does this revolutionary vocabulary resonate with you now?

Elske Rosenfeld –It is true that this project has accompanied me for a long time. 2013 was when I first formalized my research under the title “A Vocabulary of Revolutionary Gestures” into a number of gestures and corresponding artworks and texts. However, my interest in revolution, and in particular the events of 1989/90, dates back much further. If you will, it began in 1989/90 when I, as a young person, joined the protests in the streets in my hometown in Halle. The months from the first demonstrations in October 1989 to the so-called German reunification in October 1990 were politically formative for me. I got deep into the practices of self-emancipation that we lived through collectively: the discussions which I took part in, for example at school and during political marches and meetings, about how to organise a more just, democratic, equitable, and also ecological society. I was equally deeply disappointed when the accession of the GDR to the Federal Republic cut this powerful reappropriation of collective life short. The takeover of the revolution into a different – conservative, nationalist –project not only put an end to the practices of bottom-up self-empowerment and collective debate that I had lived through, but also eradicated these from the realm of the politically imaginable once more. I have come to experience this disconnect between how the history of this revolution has come to be told – as a restoration of national unity and the triumph of capitalism or liberal democracy – and the radical self-enfranchisement that I experienced and practiced as a protagonist as a form of speechlessness. But this disconnect, this perceived gap, has also stayed with me as strong impulse to think and to create.

The idea to approach this gap and this experience through the notion of gesture – that is through a number of figures that connect somatic, geometrical, philosophical and affective aspects of revolution – arose from a number of observations: Firstly, there was the fact that whenever I tried to talk with other protagonists about the events, our shared inability to find a fitting language manifested not just as an absence or lack, but also as a bodily animation. My conversation partners were dismissing our self-empowerment and our visions in the vocabularies that dominant historiography has made available to us: as “naïve”, as “utopian”, as always already doomed to fail. But at the very same time their bodies were alive with all of the things these words could not contain: the hope, the joy, the disappointment and pain – which were all so quick to come to the surface, as if no time had passed since 1990 at all. The second important insight, or let’s say methodological cue, came in 2011, with the beginning of the new wave of global revolutions and movements: the Arab Spring and the occupy movements that it inspired. People talk about “triggering” in a negative sense, where the story of another makes you re-live an old trauma. But for me, following the uprising through the news, but more importantly also through the facebook feeds of some Egyptian friends, tapped directly into my own earlier experience. Talking to my friends from Cairo, and later also friends in Istanbul during Gezi, and then again, more recently, with people involved in the uprisings in Ukraine in 2014 and Belarus in 2020, I felt that there was finally a new chance to work on a shared vocabulary – across times and places – for what we all in our different contexts and locations lived through.

The “Vocabulary of Gestures” was a way to formalize and work with these insights. Following reporting and documents from these different events, I amassed a collection of actual images as well as more abstract motifs – physical, geometrical, temporal figures and physical movements and gestures – that repeated themselves across all of these different places and times. These became the starting points of artistic and textual articulations, like the artworks of the “Archive of Gestures” described above. In these works, the gestures become hinges between different historical events, making it possible to think about 1989 through footage from Cairo or Istanbul or Minsk – and the other way around. Not only was I able to learn something about 1989 through its resonances with these present uprisings, but my work on 1989 seemed to resonate with the protagonists of these events – just as it did with you. These moments of mutual recognition and exchange are the tools, but at the same time also the rewards of my work.

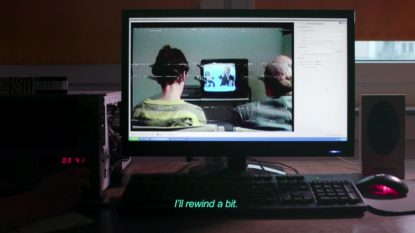

BÜ – At the Biennale last year, you exhibited four installations from this research as an “Archive of Gestures.” In Speaking (Statements for the Future), a 1-channel video installation from 2019/2022, you are reperforming declarations, manifestos, and demands made by political figures and groups in the uprising in 1989/90 in the GDR. In Interrupting (A bit of a Complex Situation), a 2-channel video-installation from 2014, you conduct a close reading of a scene from the same period, in which a Round Table meeting of representatives of the state and the new political groups in the GDR is interrupted by the sounds of a demonstration gathering outside. Circling (Another Round) was a new video installation, where you “revolve/circle” around the camp on Tahrir square after the end of a wave of protests: an edit of a video you shot spontaneously during a visit to Cairo in 2012, where an Egyptian friend and you try to come to terms with the end of a protest as a particular historical moment. And in the site-specific video installation Standing Still (Standing Man/Centers), also from last year, you invite us to “stand” before – or behind – the Standing Man at the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul in 2013. A fifth work, Repeating (Versuche/Framed) from 2018, which you included via a QR code to be watched online, is a re-framing of some footage that had initially been shot for campaign video for one of the former citizens’ movements in 1990 and shows protagonists rewatching footage of themselves from a year before, at the Round Table.

ER – The “Archive of Gestures” was a way to show the different works of the project in the way they were conceived, namely, in relation to each other. Each of these works exists only because I was able to think these different historical moments through each other. This new iteration of my project also has an online life on www.archiveofgestures.net – a platform that I use to archive and share my research, but also to initiate new works and collaborations. This year, for example, I will add the gesture “Being In/visible” – an online collage and performance that I am developing with the Belarusian artist Olia Sosnovskaya.

BÜ – I would like to single out a word/gesture from this series; stand, or standstill; in order to dwell on the idea of the gestures as hinges between the events you have chosen to work with. In the last thirty-five years, we have witnessed the political power of standing, of stillness, from the man standing in front of the tank in Tiananmen Square, to Rachel Corrie in Gaza, to the Standing Man in the Gezi protests, and from Vida Movahhed’s headscarf protest in Iran to the thousands of women in the feminist uprising today. That brilliant article written by L from the streets of Iran[1], which received a lot of attention in many places last year, was emphasizing the silent action of Vida Movahhed, in contrast to the women who made videos to verbalize their outrage. She compared the powerful impact of the circulation of Vida’s photographic image with these videos. For her, the image of this standing figure was “a transition from the narration of an everyday circumstance to the creation of a historic situation.” A moment of silence that intensifies all the problems in a single image, without establishing a representational link. A photographic image, circulating from one hand to another, of a figure who revolts against the way life just goes on, disrupting the flow and continuity. I find it very insightful when she emphasizes that this image of standstill embodies a promise and the way she connects the stillness with the mobilization of people. Strikes, occupations, blockades, that is, actions to stop the flow, have recently been on the rise again in different geographies. “That things ‘go on like this’ is the catastrophe”, Walter Benjamin’s well-known phrase, is like the motto of current struggles.

ER – Yes, this text by L was beautiful! Her text talks so powerfully not only about standing still – persisting, taking a literal stand as well as arresting time to create an image –, but also about a circular relation between protest and image and, of course, a practice of mimicry, and repetition. For me, the images that Iranian activists create, or rather, become, as they inhabit certain poses, are militant images – that is, images that are, as you rightly said, not about representing the revolt to the outside, but about keeping it going. This way of using images is something I observed in many of the recent revolts. In Cairo, in 2012 for example, I was impressed by the work of activists from the Mosireen Collective/Tahrir Cinema, who were screening footage from recent protests in impromptu outdoor “cinemas” set up in different popular neighbourhoods – which performed precisely that function at the time.[2] When I was in Istanbul in 2014, one artist we spoke to told us that there was an agreement – whether spoken or unspoken I cannot remember – that artists should refuse the demands of the international art community for instant images, instant representations of the protests. I found this a very powerful position to take; avoiding among other things, the instant commodification of protest[3], even for the “alternative” economies of attention of the critical art world.

In my work on 1989, I also look at how images were used in the revolutionary process, albeit with the more limited technological possibilities of the time. The footage of the Round Table that I use in Interrupting, for example, appears to me to be part of what I would call a militant film practice. During the Round Table’s first meeting, an independent documentary filmmaker, Klaus Freymuth, had been invited to record the session informally. He was there as a member of one of the new political groups. He then went and positioned himself and his camera not at the best vantage point, that is, a place from where he would get a “good” frontal shot, but, in accordance with his political affiliation, behind the oppositional side to which he belonged. This positioning produces a particular, skewed image, where the row of faces and bodies on the most active – the oppositional – side of the Table are seen from the side, from slightly behind. This way, their bodies are staggered one behind the other, often blocking each other out or merging into one body with multiple heads or limbs. The fragmented and fused collective body, that is produced by this affected camera is fascinating to me. But my work also asks about the political function such images can take on after the revolution, when they testify to a historical reality that has disappeared, or been erased from the historical narrative, but might still be recovered through such documents.

BÜ – It is indeed curious to see how positioning oneself changes the way one remembers the past. As long as we are not in an active effort to keep the memory of our own experience alive, the language of the sovereigns sitting on the other side of that table, sinks into our language too, as you just said, by making us see ourselves as naïve utopians. People who crack open the doors to another world with their own hands and experience social liberation through their own bodies, whether in Gezi or in another geography, eventually end up reproducing the sovereign discourse. Once the trajectory of our thinking is reduced to the binary of success and defeat with regard to criteria such as disorganization, lack of a leadership or political agenda, failure at overthrowing the government, etc., we cannot explore the layers of our struggles that we could not recognize at the time. The subsequent feeling of pessimism and surrender, the trivialization of one’s own power, that comes in the aftermath of the event, must have something to do with this fact.

You say in one of your articles in the context of art: “Western understandings of art made not only East German art practices disappear from view, but also, and perhaps more crucially, the material and discursive contexts in which their aesthetics and politics could be read.”[4] I think what causes that constitutive amazement in events like Gezi, what causes us to perceive things in a completely different way, stems from the fact that we set up new “contexts”, or in other words, we set up our own stage, as Georges Didi-Huberman emphasizes, the stage on which our political expressions appear.[5] Therefore, in the wake of the event, or to say, after the stage disperses, we need more insights that can resist the colonization of our minds and that rationalize these exceptional moments of collective experiences. In the absence of such revolutionary moments, art provides us with a context in which to carry out these experiments, and artistic practices like yours provide the toolkit for them.

ER – You are addressing a very important point here: the fact that recent revolts and revolutions are not produced by, but must produce the vocabularies – the sense-making contexts or “stages” – in which their success or failure can be discussed. One thing that the revolutions from 1989 onwards have in common is that, just as they don’t tend to have any clear leaders, they also lack a prior vision or blueprint for a post-revolutionary future. This lack of a clear goal has often been thought of as the reason behind these revolutions’ or protests’ failure to achieve real, structural change. But I think that the disappointing outcomes of these revolutions were not so much the product of their internal failure, – their lack of coherent visions, or their internal contradictions – as of their defeat (this a distinction I take from Bini Adamczak’s writing on the Russian revolution) from the outside. Different sets of players, either from among the old elites, or, in the East German case from among the ruling West German conservatives, often with much more ample resources, imposed their own agendas, before the revolutionary process itself has the chance to institutionalise into its own new political and societal forms. And with this takeover also ends the process in which the revolution creates its own language – with the result you describe above: that the revolutionaries have to borrow the unchanged vocabularies of the status quo (or as Benjamin put it, of the victors of history) to make sense of their own history. Art can then become a space, where those parts of the revolutionary experience that become unintelligible in this dominant historiography, can once more be shared.

BÜ – In her writings on Paris Commune and May ’68, Kristin Ross also includes the approaches of sociologists and historians among the external factors that feed into this “defeat” narrative. Sociology, she says, “has always set itself up as the tribunal to which the real—the event—is brought to trial after the fact, to be measured, categorized, and contained.”[6]

ER – Which is a pity, because a more militant form of sociology might be a great tool for approaching the new politics that these revolutions unfold in their lived forms. You know this of course, from the camp at Gezi Park: how it organized basic necessities such as food, shelter and protection, without leadership in the traditional sense. For the Egyptian case, Asef Bayat[7] has done wonderful research into these forms of self-organisation that explode during uprisings and occupations, but also predate and outlive the revolutionary period to some degree. I think there is work to be done, both on the empirical and the conceptual level to understand how revolutions unfold their politics as practice, often even beyond their actors’ own intent or comprehension. We need political concepts and methodologies that go beyond the older Marxist understanding of revolution as system change, but also beyond more recent concepts of the Political as a mere interruption, mere negation, like that of, for example, Jacques Rancière. Feminist approaches that look at the day to day of revolution are useful here, like those of Judith Butler[8], Veronica Gago[9], or Ewa Majewska[10], all of who have developed their analyses of recent revolts and revolutions close to their participants’ bodies. They understand the politics of revolution as something that happens between the registers of the minor and the major: between those “small” acts of care and sustenance, that earlier feminists have allowed us to recognize as political, and the revolutions’ exceptional “heroic” moment. What I find so helpful about these approaches is that by looking for the ordinary in the extraordinary, they also allow us to find the potential for radical change in the most unexceptional everyday. In my work I am interested in this question of how the revolution manifests in bodies – but also in how it survives there as an emancipatory knowledge or impulse after a revolution’s declared end. I think this is where my work on the revolution of 1989/90 – in my art projects, but also in my upcoming book – can add something to the conversation, simply because in this case the tension that exists between official history and an embodied counter-knowledge has been there for a much longer time.

BÜ – Let’s also talk about the physical tension in bodies during the uprisings, taking another example from the “Archive of Gestures”. On June 17, 2013, two days after the police forcibly evacuated Gezi Park, the eight-hour long still-act of Duran Adam (the Standing Man, Erdem Gündüz) took place. And with that, the police not knowing what to do, the staggering effect it had on the raison d’état, the people who appeared in squares all over Turkey and stood for days… And this time, Duran Adam is standing in the center of Berlin, inside the Akademie der Künste building on Pariser Platz, on the threshold of its glazed façade. You placed two parallel monitors connected to one another by a metal structure. One monitor displays Erdem’s face and turned towards the biennial site, in a position to welcome those entering the building. The other monitor displays his back, facing the Brandenburg Gate, and the parliament building a little further away. With this set-up, it appears to be a digital sculpture of resistance for tourists, exhibited on the edge of the square. There is also an impressive contrast between the sumptuous rearing of the imperial symbol quadriga above the Brandenburg Gate and the standstill of Duran Adam. When we put on the headphones, we hear the sounds of Taksim Square and of Vito Acconci’s 1971 video work, “Centers”, in which he stands still for 23 minutes with his index finger pointed at the camera. The gesture that characterizes Duran Adam and Acconci’s work is standstill. Both performances are characterized by persistence, tenacity and even stubbornness. Both play with the audience’s expectation of progression and change, the expectation of a transition to a new state. And the “new” does not emerge. The social tension generated by that expectation is joined by the tension that condenses in the artist’s body, in the muscles, nerves, joints. Therefore, what we name as standstill is actually a challenge, a threshold experience between the psycho-physical dynamic inside the body and the social dynamic between the body and the exterior. As an artist, you take over this persistence and steadily point your camera at these gestures or hold your microphone to their sounds, both replicating and amplifying them and intervening in them and the way they are received.

ER – My work with Erdem Gündüz’ gesture differs from my other works with found footage in that it is a dialogue with another artist (or, I should say, with other artists, because I also respond to Vito Acconci’s work, as you rightly point out). Gündüz’ gesture is an artwork as well as a form of protest and it is extremely rich. I am glad that you picked up on some of the aspects of his gesture that my work responds to and riffs off on, as it moves the gesture into this specific location and the context of an art exhibition. Let me add a few more thoughts. One thing that interested me is that Gündüz produces a temporary sculpture and I would say, a non-heroic sculpture, in the sense that the sculpture is made up of his living body which makes it absolutely impermanent and vulnerable. For the sound that one hears through the headphones, I used samples from video footage I found online, where Gündüz is searched by the police who touch Gündüz’s body all over, which is very violent. In my rendition, by being integrated into an upright metal structure, Gündüz’ gesture becomes even more sculptural – it becomes a kind of monument. But it is still not static, it is, in fact, trembling. By filming the photos of Gündüz’ protest with a handheld camera, the still image that his gesture turned into and that then circulated across the globe is reanimated. This way, standing still is revealed as the multiplicity of micro-movements, the dense vibration that it actually is, physiologically speaking. But this time it is my body, not Gündüz’, that is trembling and producing an image that is shaken up, that is instable, unfixed. The minimalism of my intervention (or non-intervention) repeats the minimalism of his gesture. In my work this minimalism becomes an invitation to the viewer to become still, to slow down in watching. I am interested in the possibility that, if the viewer quietens herself, she might attune her perception to notice more, in the work, around the work, in herself.

Thirdly, as you rightly observe, the positioning of the monitors is important. On Taksim Square, Gündüz was facing a portrait of Atatürk. Some of my Turkish friends are uncomfortable with his gesture, because of this Kemalist, nationalist orientation. In my take on the gesture, of course, Gündüz turns his back on the Brandenburg Gate – a national symbol, or a symbol of nationalism, that has a particular resonance for me as an East German. It is, of course, my back, that is turned to the symbol of the German unification, and the way it happened that was anathema to my experience of and my hopes for that revolution. That said, the site-specificity of the installation at the Akademie der Künste was an added layer for me. The idea for this work predates the invitation of the Biennale and, as it were, stands on its own for me.

BÜ – The struggle over symbols also seems to be escalating. We live in a time when “heroic” statues and monuments symbolizing colonialism are toppled and the work on decolonization is intensifying. Meanwhile, in the heart of Berlin, a replica of the imperial palace has been rebuilt on the rubble of the GDR parliament. Named the Humboldt Forum, it opened as a museum in July, 2021. In Germany, the GDR past is, if not a taboo topic, a narrative that strictly focuses on its oppressive aspects. When I came to Berlin a few years ago, I attended a German language course. In one of the lessons on the history of Berlin, I was quite surprised by the way in which the GDR past was presented. Imagine, you are in a language course, you have just arrived, you don’t know anyone and you find yourself in the midst of anti-communist propaganda. As though this was the worst, repressive, shameful period in German history, and foreigners should have been informed about it immediately. Even in the films on the GDR that I sometimes saw at festivals, I found that a narrative of trauma was dominant. Was there really not a single positive impression or experience? A dynamism that we can draw from the past to the present, revolutionary aspirations, dreams or wishes that can feed current struggles? In that sense, it seemed to me like there was a strange silence about the GDR in general.

ER – Of course the experience of living in the GDR was not all negative. People lived complex, contradictory and rich lives under, despite and in response to the model of socialism that had been implemented by this country’s rather dogmatic and paranoid regime. The memory of the GDR is woven through with different traumas, some of which pertain to experiences of violence and repression in the GDR, some of which pertain to the trauma of the biographical, social and economic rupture after unification, and some of which are, finally, connected to the revolution itself, the hopes it raised and then failed to redeem. The trauma caused by the repressive nature of the East German state – itself a result of the failure of the emancipatory project of state-socialism in its Leninist and Stalinist mould – is a complex issue and one that has not been served well by the simplifying, reductive, and largely ideologically motivated anti-communist forms of commemoration and historicisation the unification has put into place. The process of undoing and complexifying this narrative is a formidable task that is only just being taken up.

Regarding the trauma of the economic shock transformation and cultural erasure during the 1990s there has been a big shift in recent years from a purely celebratory attitude to the (post-)unification to a more factual approach. A younger generation of east Germans, that grew up during those years have begun to enter the media and other institutions in a way earlier generations had not – and have been able to break the silence surrounding those years. It has become possible to speak of the unification as failed or at least as partially failed.

However, what interests me in particular, and what I believe is still completely, and tellingly missing from this conversation, is the trauma of the end of the revolution. This is the speechlessness about the revolution that I talked about in the beginning – and a phenomenon that I have heard people talk about with regard to other revolutions und political movements – Gezi, the Arab spring, the Solidarność movement in Poland in the early 1980s – that are considered as failed. This is the trauma of having invested yourself wholeheartedly in a project of self-empowerment that was then defeated and, after being defeated, dismissed by the new or old custodians of the status quo as utopian, misguided, or naive. This left people embarrassed by their own former hopes, by their belief – which was in fact not a mere belief but a lived, if brief, experience – that it is possible to reorganize life collectively, based on a presumption of equality.

Unlike the trauma of the neoliberal shock transformation that can now be talked about because it is, in fact, over, the conditions that created the trauma of the post-revolution are still with us. The sense of disenfranchisement that followed a great self-enfranchisement remains unbroken – we are still in the post-revolution, in this sense. Which makes this trauma much harder to see and talk about. In Germany, the disappointment that many post-revolutionaries felt after unification was quickly depoliticized and pathologized. Almost two decades of east German discontent and protest (against the mass privatisations of the early 90s, and against the social cuts of the early 2000s) have been filed away as irrelevant under the trope of the “Jammerossi” – a depiction of east Germans as ungrateful and unpolitical. It is only after the protests took a drift to the right – in their language and aims – after 2014 that they were taken seriously. This again, is a big topic, but, I think, an important one that ties the question of the historicisation of revolt and revolution – the question of an adequate vocabulary for its enduring emancipatory promise – intimately to our ability to respond to the crises of the present. It hugely impacts people’s trust in their ability to shape their own future or, conversely, their susceptibility to the authoritarian counter-offer. In this sense, I see both our work on the (counter-)narrativization of the emancipatory projects we lived through in the GDR in 1989, in Turkey in 2013 as much more than pure historiography: as the arena in which our ability to act in the present comes to be either constrained and closed down or bolstered and expanded.

Burak Üzümkesici holds an MA in Art History from İstanbul Technical University and is currently a PhD candidate in Philosophy at Freie Universität Berlin. His areas of research mainly focus on forms of political action, artistic practices, mimesis theory, media and mediation.

References:

[1] “Figuring a Women’s Revolution: Bodies Interacting with their Images”, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/44479 and https://www.e-flux.com/notes/497512/women-reflected-in-their-own-history.

[2] For Rosenfeld’s speech in Cairo in 2012, see “Pictures that refuse to go back inside. An artist talk on revolutionary images”, https://www.eipcp.net/projects/creatingworlds/rosenfeld/en.html

[3] For a recent and an important discussion on the commodification of protests in the context of Iran, see “The Commodification of Jin, Jiyan, Azadi (Woman, Life, Freedom) by Art Institutions in the West”, https://www.another-screen.com/films-from-iran-for-iran

[4] “Signals, Gestures, Collective Bodies”, http://dissidencies.net/signals-gestures-collective-bodies/

[5] Georges Didi-Huberman, “Conflicts of Gestures, Conflicts of Images,” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 27, no. 55–56 (2018): 8–22.

[6] Kristin Ross, May ’68 and Its Afterlives (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 4.

[7] Asef Bayat, Revolutionary Life: The Everyday of the Arab Spring (Harvard University Press, 2021).

[8] Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, Reprint edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: Harvard University Press, 2018).

[9] Veronica Gago, Feminist International: How to Change Everything, trans. Liz Mason-Deese (Verso, 2020).

[10] Ewa Majewska, Feminist Antifascism: Counterpublics of the Common (London: Verso, 2021).