Sinyaller, Jestler, Kolektif Bedenler

Signals, Gestures, Collective Bodies has now been published on [https://www.5harfliler.com/sinyaller-jestler-kolektif-bedenler/] in a translation by Burak Üzümkesici*.

Read MoreDemokratik Alman Cumhuriyeti’nde (Doğu Almanya) kadınların özgürleşmesi işçi sınıfının özgürleşmesine bağlı olarak düşünülüyordu. Cinsiyet eşitliği Doğu Almanya anayasasında yer alıyordu, dolayısıyla bu mevzuya sosyalist devlette artık bir sorun olmaktan çıkmış gözüyle bakılıyordu. Oysa gerçekte kadınlar devlet kurumlarının ya da şirketlerin üst kademelerinde nadiren yer bulurken, bir yandan da tam zamanlı çalışma ve ev içi yeniden üretim emeğinin çifte yüküyle cebelleşiyorlardı. Bu eşitsizlik ve çelişkiler Doğu Almanya’nın muhalif çevrelerinde dahi nadiren politik bir sorun olarak görülüyordu. Söz konusu çelişki ve eşitsizliklerde bir sorun görmek ya da kendini “feminist” olarak nitelemek, doğrusu, pek tasvip edilen bir şey değildi.[1] Bu çevrelerde aktif olan kadın sanatçılar devlet karşısında kendilerini erkeklere kıyasla daha muhalif bir konumda hissediyor[2] ve kendi özgürlüklerini yeraltı kültürünün erkek-merkezli ideallerini yıkmak ya da bunlara direnmek yerine, çoğu zaman bunlara öykünmekte arıyorlardı.[3] Annemirl Bauer ya da Angela Hampel’inkiler gibi toplumsal cinsiyete ya da “kadınlığa” doğrudan referans veren çalışmaların sayısı ise azdı.

Erfurt’lu sanatçı Gabriele Stötzer’in (d. 1953, Emleben, Thüringen) işbirliğine dayalı performansları ise, sosyalist devletin kolektiflik, toplumsal cinsiyet ve sanat kavramlarına yüklediği anlama meydan okurken, aynı zamanda kendisinin de bir parçası olduğu ülkenin muhalif ve yeraltı sanat çevresinin yaklaşımından da kopuyordu. Bu çevre, (erkek) sanatçının otonom bedenini sosyalist sistemin taleplerine karşı eşsiz bir sığınak olarak görürken, Stötzer’in sanatı ise en çok da azami ölçüde merkezsiz, parçalı ve dünyaya açık olduğunda özgürleşen muhalif, dişi ve kolektif olarak şekil verilen beden üzerinde kafa yoruyordu.

Bu metin, sanatçının kırılganlıkların vücut bulduğu biraradalık biçimleri oluşturmaya dayalı pratiğinin kendine has feminizmine adanmıştır.

Derin bir Fiziksel Altüst Oluş Deneyimi Kolektif bir Sanat Pratiğine Yol Açıyor

Gabriele Stötzer (o zamanlar evlilik soyadı olan Kachold ile tanınıyordu) başlangıçta memleketi Erfurt’un muhalif edebiyat ortamında aktif biriydi. İşbirliğine dayalı ve beden odaklı kendine has performatif pratiğini ise, benlik algısını ve dünyasını fiziksel ve zihinsel düzeyde allak bullak eden bir deneyimden sonra geliştirdi. Stötzer, 1977 yılında muhalif şarkıcı ve söz yazarı Wolf Biermann’ın sınırdışı edilmesine karşı yazılan ünlü ortak bildiriyi imzalayıp dağıttığı için tutuklanarak hapse atıldı. Şiddet veya siyasi suçlardan hüküm giyen kadın mahkûmların kaldığı, “katiller kalesi” olarak anılan meşum Hoheneck hapishanesinde yedi ay geçirdi.[4] Hapishanenin fiziksel ve psikolojik açıdan son derece zorlayıcı koşulları altında mahkûm arkadaşlarıyla yaşadığı karşılaşmalar, Stötzer’in kendisine, cinsiyet fenomenine ve Doğu Almanya’nın sosyalist modeline dair algısını derinden sarsacak ve değiştirecekti. Gabriele Stötzer sonraları hapishane günleri hakkında konuşurken, “Doğu Almanya’ya ve kadınlara bakışı[nın] bir anda yerle bir olduğunu” söylemişti.[5]

Mahkûm kadın arkadaşlarının, kadın katillerin, hırsızların ve fahişelerin bedenleri, Doğu Almanya’da, tezat oluşturmak şöyle dursun birbiriyle gayet iyi örtüşen iki kadın bedeni konfigürasyonuna meydan okuyordu: bir yanda geleneksel “iyi aile kızı”[6] (küçük) burjuva kadının bedeni, diğer yanda eski burjuva idealinin yerini almaktansa tam da bu idealin üzerine oturtulmuş disiplinli ve üretken kadın sosyalist işçinin bedeni. Bunların ikisinin de hapishanedeki kadınlarla bağdaşan bir yanı yoktu: “Birbirlerine duydukları fiziksel aşk, bedenlerine yaptıkları dövmeler, kaşık yutarak intihara teşebbüs etmeleri: Ne dışarıdaki reel sosyalizm ne de ebeveynleri Stötzer’i böyle bir şeye hazırlamıştı. Kendi annesinde de bir örneğini gördüğü, Doğu Almanya rejimi tarafından ‘özgürleştirilmiş’ kadının prototipi olarak propagandası yapılan tertipli ve çalışkan anne-işçi şeklindeki kadın imgesi paramparça olmuştu.”[7] Stötzer’in kendi sözleriyle, [mahkûm kadınların] “bendeki kadın imgesiyle zerre uyuşmayan hayat hikâyeleri ve karakterleri”[8] vardı.

Gabriele Stötzer tahliyesinin ardından, yaşadıkları hakkında konuşamadığını ve başından geçenlerin zihninde imgeler halinde canlandığını idrak etti. Esasen siyasi faaliyete yönelen diğer eski siyasi mahkûmların aksine Stötzer kendini şiir ve sanata yönelmiş buldu. Hapishanede yaşadığı şiddetli kırılmanın ardından (cinsiyetlendirilmiş) benliğinin kolektif olarak yeniden kurulması gerektiğini, bunun da tek başına başarılamayacağını farketti. Stötzer, yaratıcı süreci için ihtiyaç duyduğu katılımcıları bulmak adına, devlet kurumlarıyla kendisi gibi olumsuz deneyimler yaşamış kişilerle, genellikle de kadınlarla bir araya gelmeye başladı. Doğu Almanya Devlet Güvenlik Bakanlığı (Stasi) tarafından sürekli maruz bırakıldıkları gözetim ve engellemelere rağmen, kadınlar haftada bir kez Stötzer’in özel galerisinde veya fotoğraf laboratuvarı ve stüdyoya dönüştürülmüş yıkık dökük işgâl evlerinde buluşuyorlardı.[9] Bu buluşmalarda rüyalardan konuşuyor, vokal ve ses deneyleri yapıyor[10] ve kendi yaptıkları kıyafet ve aksesuarlarla, bazen de onlar olmadan birbirlerini fotoğraflayıp filme alıyorlardı. Kadınların kendi sınırlarını zorlamalarını mümkün kılan bu güven ilişkisinin temelinde yatan şey ise kurdukları dostluklardı. Stötzer bir keresinde bu kadınlarla yaptığı çalışmaları bir tür takas olarak tanımlamıştı: “Kadınlara bedenlerini bir deneyim, bir his, bir duyumsama, kadın cinsiyetine dair yanıtlanmamış sorularının oluşturduğu eşiği aşma tecrübesi olarak geri vermek dışında bir şey sunmayan” bir takastı bu.[11]

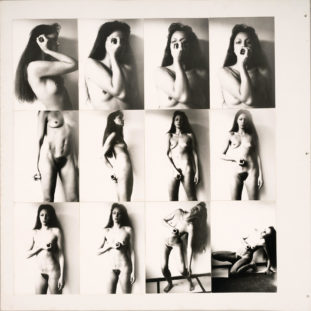

Gabriele Stötzer, The Hole [Delik], und, frauen miteinander, [ve, kadınlar birlikte] fotokitaptan, 1982/3, sanatçının izniyle

Stötzer’in çağrısı zamanla giderek artan sayıda kadını (hatta bazı erkekleri de) sanatının ayrılmaz parçası haline gelen “kolektivist bir çalışma ve yaşam anlayışına”[12] doğru çekti ve bunu yaparken de sanat-toplum ilişkisine dair eski Sosyalist Gerçekçi yaklaşımları olduğu gibi, emsallerinin bu yaklaşımlara yanıt olarak geliştirdiği “underground” veya “aykırı” sanat formlarını da bozguna uğrattı.

Çifte Kaçış: Doğu Almanya’da ve Onun Underground Dünyasında Patriyarkal Tahakküme Direnmek

Stötzer’in kuşağından pek çok sanatçı için devletin boğucu ideolojik tasallutundan kaçış “yeraltı”nın içe kapanık, homojen çevrelerine ve alenen apolitik bir sanata ricat etmek anlamına geliyordu. Erkek olarak tasavvur edilen bireysel sanatçı bedeni, sadece (bireysel) sanatsal yaratımın kaynağı değil, aynı zamanda rejimin taleplerine karşı isyanın ve özgürlüğün mevzisiydi de. Başına buyruk, “özgür” erkek bohem sanatçı figürü baştacı ediliyordu [13].

Bundan dolayı, Gabriele Stötzer’in kadınlarla, kadınlık hakkında çalışma kararı gerek Doğu Alman devleti, gerekse birlikte hareket ettiği muhalif çevreler açısından provoke edicidir. Stötzer, 1984 yılında, Doğu Almanya’da bulunan yegâne kadın sanatçı topluluğu olan Künstlerinnengruppe Erfurt’u (sonradan Exterra XX adını alan Erfurt Kadın Sanatçılar Grubu) kurdu. Yıllar boyunca Monika Andres, Tely Büchner, Elke Carl, Monique Förster, Gabriele Göbel, Ina Heyner, Verena Kyselka, Bettina Neumann, Ingrid Plöttner ve Harriet Wollert’in yanı sıra Ines Lesch, Karina Popp, Birgit Quehl, Jutta Rauchfuß ve Marlies Schmidt grubun faaliyetlerinde yer aldı ve katılımcı sayısı zamanla daha da arttı. [14] Grup, çalışmalarında yeraltı ile devlet arasında ikili bir karşıtlık kurmak yerine, her ikisinde de mevcut olan patriyarkal tahakküm biçimlerini ele alan deneylere girişti. Grup içinde teşvik edilen sosyalleşme ve elbirliğinin yarattığı güvenle kadınlar, toplumsal cinsiyet ve normların dışında ve bunlara karşı kendilerinin ve birbirlerinin bedenlerini keşfettiler.

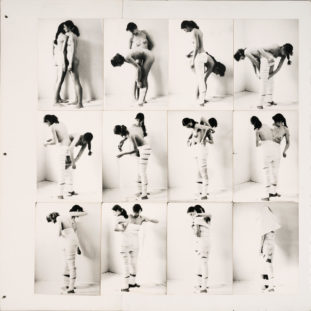

Kendilerini eşit ölçüde patriyarkal olan rejimin ve yeraltının çift yönlü saldırısından kurtarmak için, artık kendisi de bir tahakküm biçimi olarak deneyimlenen sözümona özgürleşmiş, erkek, bireysel sanatçı bedenine sığınamazlardı. Stötzer’in grubunun fotoğraf ve film deneylerindeki bedenler artık birer kahraman gibi değil, yaralı, kırılgan, hassas ve dünyayla iç içedir. Bu fotoğrafların bazılarında bandajlar bir bedeni gizler, sınırlar ya da iki bedeni birbirine bağlarken, diğerlerinde bedensel açıklıklar işaretlenir ya da ellerle gerilerek açılır, deri esnetilir, çekilir ya da boyanır. Kendini özgürleştirmek, bu işlerde radikal biçimde kolektif, başkalarına açık ve merkezsiz olmak anlamına geliyor. Verili toplumsal cinsiyet konfigürasyonlarının ve yeraltı/devlet siyasi ikiliklerinin ötesine geçerek, o zamanın mevcut dillerinde (henüz) ifade bulamayan varoluş biçimlerini duyumsayan ve onlarla deneyler yapan bedenlerdir bu işlerde karşımıza çıkan. Bu bedenler “yeni bir gerçeklik” için öngörüler ve deneysel konfigürasyonlar olarak işlev görüyor, diyordu Gabriele Stötzer kendi bedensel sezgilerinden yola çıkarak ve şunu eklemeyi de unutmuyordu: “bu diğer gerçekliğin adı Batı değildi.”[15]

Gabriele Stötzer, Wrapping [Sargı], und, frauen miteinander, [ve, kadınlar birlikte] adlı fotokitaptan, 1982/3, sanatçının izniyle

Yeni Bir Gerçeklik: Stötzer’in Feminist Sanatı ve Aktivizmi Birleşiyor

Signale (Sinyaller) filmi ise, grubun 1989 baharında başladığı bir projeydi ve sonunda öngörücü, hatta “kehanetvari” bir film ortaya çıkacaktı. “Sinyaller saklı kalmış bir şey hakkındaydı, henüz söze dökülüp de konuşulamayan bir şeylere sesleniyordu.”[16]

Birkaç ay sonra, grubun çalışmalarının sinyalini verdiği “yeni gerçeklik” her yerde görkemli bir varoluşa doğru taşmaya başladı. Sonbaharda devrim başladığında, yaşamın her alanı kolektif düzeyde yeniden tasavvur edilerek hızla politikleşirken, kadınların deneyleri zahmetsizce dünyaya açıldı. Feminist sanatsal işbirliklerinin örtük (ya da mikro) politikası, somut (makro) politik eylemlere dönüştü. Frauen für Veränderung (Değişim için Kadınlar) grubu Stötzer çevresinden doğdu ve bu çevrenin var ettiği maddi ve manevi dayanaklar üzerinde yükseldi: networkler, kaynaklar, beceriler, karşılıklı edinilen bilgi ve duyulan güven.[17] Grup, Erfurt’ta her hafta yapılan eylemlerde önemli bir rol oynadı ve şehrin belediye binasında ilk kez sadece kadınlar için toplantılar örgütledi.

Stötzer, 8 Kasım 1989’da bu yeni grubun 300 üyesi önünde bir konuşma yaptı:

erkeklerin liderliğine karşı

liderlere karşı

rollere karşı

imajlara karşı

son 40 yıla damga vuran kadın imajlarına karşı [18] bir konuşmaydı bu.

Bu devrimci uğrakta, Doğu Almanya sosyalizminin ideolojik, siyasi yapılanmasının, rollerin ve siyasi hiyerarşilerin parçalanması ile toplumsal cinsiyetin, patriyarkanın kendine özgü yapılanmasının çözülmesi bir ve aynı şey olarak ele alınabilir hale gelmişti. Stötzer’in işbirliklerinde birkaç yıldır irdelediği kolektif “ben”-lik ve “kadın”-lık hallerinin estetik olarak dolayımlanmış biçimleri nihayet artık sanatının dışında da kendine bir isim ve farklı bir yaşam çevresi bulabiliyordu. 8 Kasım’da, Stötzer’in sanatındaki bedensel sinyaller, kısa bir süreliğine de olsa dar bir çevrenin dışına çıkarak farklı temaslar kurabilmişti. Stötzer’in pratiğinin devlet-sosyalizmi kavramsallaştırmalarının derinleşen çatlak ve çelişkilerinden yola çıkarak örmeye başladığı, politika, sanat ve toplumsal cinsiyetten müteşekkil takımyıldız artık görünürlük kazanmaya ve mümkünün alanına girmeye başlamıştı.

1990 Sonrası: Stötzer’in Sanatı ve Politikası Batı Lügatinde Okunaksız Hale Geliyor

Devrimin yönünün 1990 kışında Alman ulusunun birleşmesine doğru sapması, bu deney ve hayallerin yok sayılarak dışlanmasıyla sonuçlandı. 3 Ekim 1990’dan sonra, Doğu Alman devleti ve onun kendine has kültürleri, genişleyen Federal Almanya Cumhuriyeti içinde eriyip yok olurken, Gabriele Stötzer ve grubunun geliştirdiği muhalif feminenlikler de unutulup gitti. Stötzer’in muhalif feminizmi de, kolektifliğin yeni biçimlerine dair giriştiği politik-estetik araştırmalar da Batı’nın artık egemen olan sözdağarlarında bir kez daha konuşulamaz hale geldi.

Feminist diller de Batı’nın kendi mücadeleleri içinde yoğrulduğundan, devlet sosyalizminin ilerici görünen sosyal ve cinsiyet politikalarının farklı cinsiyetli varoluş tarzlarını geçerli kılma ve geçersizleştirme biçimlerinin yanı sıra, bunlara karşı geliştirilen stratejileri de gözden kaçırdı. Batılı sanat anlayışları da benzer şekilde, sadece Doğu Alman sanat pratiklerini görüş alanından çıkarmakla kalmadı, aynı zamanda ve belki de daha önemlisi, bu pratiklerin estetiğini ve politikalarını okunaklı kılan maddi ve söylemsel bağlamları da sildi. Soğuk Savaş’tan miras komünist-antikomünist ikiliğine saplanıp kalan sanat tarihi analizleri ise, Doğu Almanya’nın yeraltı sanat dünyasını konu ettiklerinde genellikle, Stötzer’in pratiğinin defterini dürdüğü özgürleşmiş, otonom, deha sanatçı türünden fazlasıyla cinsiyetlendirilmiş, eril çağrışımlı yaklaşımları yineleme eğiliminde oldu. Hülâsa, Stötzer’in pratiği uzun yıllar boyunca yeterince ilgi göremedi.

Gabriele Stötzer ve grubunun çalışmalarına yönelik ilginin artıyor olması iyi haber. Onların film ve fotoğraflarda muhafaza edilen bedenlerinin günümüze ilettiği sinyalleri; farklı ve uzlaşmacı olmayan cinsiyetlerden aktarılan bilgi ve olanakları deşifre edip açığa çıkarmak, özverili ve titiz bir feminist çalışmayı gerektiriyor. Önümüzde, bu feminist mirasın cevherlerini gün yüzüne çıkarmak gibi harika bir görev duruyor.

Notlar

[1] Angelika Richter, Das Gesetz der Szene: Genderkritik, Performance Art und zweite Öffentlichkeit in der späten DDR (Bielefeld, 2019), s. 136. [2] A.g.y., s. 144. [3] Doğu Almanya’da (sanat çevreleri de dahil olmak üzere) kendilerini devletin ve kurumlarının karşısında konumlandıran ya da devlet tarafından eleştirel veya muhalif olarak görülen birey ve grupları tanımlamak için çeşitli terimler kullanılmıştır: karşıt, muhalif, aykırı, underground, vs. Ancak, bu terimlerin hiçbiri, özellikle de öznelerin kendilik algıları söz konusu olduğunda, resmin tamamını yansıtmamaktadır. [4] Claus Löser, Strategien der Verweigerung: Untersuchungen zum politisch-ästhetischen Gestus unangepasster filmischer Artikulationen in der Spätphase der DDR (Berlin, 2011), s. 290. [5] “Gabriele Stötzer: Anklagepunkte,” n.d., zeitzeugen-portal, Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UwGwd6dS-uE (linklere son erişim: Haziran 2022). [6] Rebecca Hillauer, ‘Zeit hinter Mauern,’ der Freitag, 18 Ekim 2002, sec. Kultur, http://www.freitag.de/autoren/der-freitag/zeit-hinter-mauern. [7] A.g.y. [8] Stötzer’den aktaran Karin Fritzsche ve Claus Löser, Gegenbilder: Filmische Subversion in der DDR 1976–1989; Texte, Bilder, Daten (Berlin, 1996), s. 75. [9] Yazarın Stötzer’le yaptığı söyleşiden. [10] Löser, a.g.y., s. 294. [11] Fritzsche ve Löser, a.g.y., s. 76. [12] Löser, a.g.y., s. 296. [13] Richter, a.g.y., s. 108. [14] A.g.y., s. 131. [15] Fritzsche ve Löser, a.g.y., s. 76. [16] Yazarın Stötzer’le yaptığı e-posta yazışmasından, Mayıs 2013. [17] Örneğin Stötzer ve çevresinden dört kadın, ülkedeki ilk başarılı Stasi bölge karargâhı işgâlini başlatacak ve bunu kısa süre sonra başka yerlerdeki işgaller izleyecekti. Bkz. Peter Große, Barbara Sengewald ve Matthias Sengewald, “Die Besetzung der Bezirksverwaltung des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit der DDR am 4. Dezember 1989 in Erfurt,” Gesellschaft für Zeitgeschichte, n.d., www.gesellschaft-zeitgeschichte.de. [18] “geredet im rathaussitzungssaal vor frauen eingeladen von der bürgerinneninitiative frauen für veränderung am 8.11.89 gegen 22 uhr,” adlı belge, Gabriele Stötzer’in kişisel arşivinden.*Burak Üzümkesici holds an MA in Art History from İstanbul Technical University and is currently a PhD candidate in Philosophy at Freie Universität Berlin. His areas of research mainly focus on forms of political action, artistic practices, mimesis theory, media and mediation.